–

What then must we do?

–

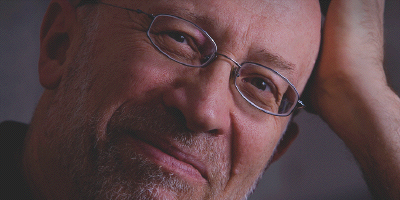

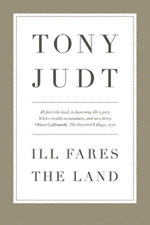

Ill Fares the Land

Ill Fares the Land

By Tony Judt

(New York: Penguin, 2010)

Ill Fares the Land makes for a brisk if chilling read. “We have entered an age of insecurity: economic insecurity, physical insecurity, political insecurity,” it begins. “The last time a cohort of young people expressed comparable frustration at the emptiness of their lives and the dispiriting purposelessness of their world was in the 1920s.”

I knew about the 1920s from my grandfather, Whittaker Chambers.

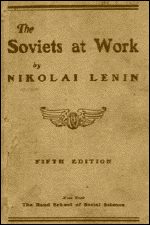

In 1923, he visited Western Europe, still lying in the ruins of World War I. By 1925, he saw a “dying world… without faith, hope, character” [Witness, p. 195]. He came across a little book by Lenin called The Soviets at Work that won him over to Communism. Still, when later defecting from the Soviet underground, he shared a curious doubt with my grandmother. “We are leaving the winning world for the losing world.”

In 1923, he visited Western Europe, still lying in the ruins of World War I. By 1925, he saw a “dying world… without faith, hope, character” [Witness, p. 195]. He came across a little book by Lenin called The Soviets at Work that won him over to Communism. Still, when later defecting from the Soviet underground, he shared a curious doubt with my grandmother. “We are leaving the winning world for the losing world.”

Losing? Followers of William F. Buckley, Jr. , say this was my grandfather’s one truly false prediction [see Spectator, Claremont Review of Books, First Principles, National Review, American History, Commentary]. However, such people rarely consider a basic truth about “the losing world.” Mr. Judt notes it, though. “Unregulated capitalism is its own worst enemy; sooner or later it must fall prey to its own excesses”

Ill Fares the Land picks up on this old doubt about capitalism. It comes with near-perfect timing — on the heels of the ongoing global financial crisis. Without the bombast of the Old Left, it questions capitalism’s survival. Mr. Judt offers real-world analysis of history, rather than Chambers’ personal abstractions from ideals. His thoughts come from decades of study, rather than decades of political fighting (in writing) like Chambers. Best to read Ill Fares the Land right after Mr. Judt’s magnum opus, Postwar, as a critical coda that asks bluntly, what next?

Ill Fares the Land picks up on this old doubt about capitalism. It comes with near-perfect timing — on the heels of the ongoing global financial crisis. Without the bombast of the Old Left, it questions capitalism’s survival. Mr. Judt offers real-world analysis of history, rather than Chambers’ personal abstractions from ideals. His thoughts come from decades of study, rather than decades of political fighting (in writing) like Chambers. Best to read Ill Fares the Land right after Mr. Judt’s magnum opus, Postwar, as a critical coda that asks bluntly, what next?

Mr. Judt is an excellent writer. He riffs on the Communist Manifesto, turning its famous opening (“A spectre is haunting Europe“) into disquiet: “Something is profoundly wrong with the way we live today.” He closes with Marx’s final thesis on Feuerbach: philosophers have only interpreted the world; “the point is to change it.” I imagine my Marxist-schooled grandfather finishing Ill Fares the Land and exclaiming, “Now, this is the kind of thing I meant to write!”

While it may seem to parade in Marxist trappings, Ill Fares the Land is closer to the American book of another British transplant and radical, Thomas Paine. Paine’s incendiary manifesto, Common Sense, includes “thoughts on the present state of American affairs” and on the “present ability of America,” as does Mr. Judt’s book. To understand our 21st-century ability (or “the way we live today,” as Mr. Judt puts it), he reviews the 20th. He outlines the two main economic schools of liberal (Keynes) and conservative (Hayek & Co.) thought. He manages clear use of vocabulary nowadays so degraded by mass media that others use it only to touch hot buttons. Mr. Judt engages brains.

While it may seem to parade in Marxist trappings, Ill Fares the Land is closer to the American book of another British transplant and radical, Thomas Paine. Paine’s incendiary manifesto, Common Sense, includes “thoughts on the present state of American affairs” and on the “present ability of America,” as does Mr. Judt’s book. To understand our 21st-century ability (or “the way we live today,” as Mr. Judt puts it), he reviews the 20th. He outlines the two main economic schools of liberal (Keynes) and conservative (Hayek & Co.) thought. He manages clear use of vocabulary nowadays so degraded by mass media that others use it only to touch hot buttons. Mr. Judt engages brains.

Where Paine recommended revolution, Mr. Judt suggests milder though no less serious action. We need to discuss in public how to survive capitalism. He suggests that we continue to evolve the latest, proven approach to ameliorating capitalism. That approach — social democracy — is his starting point for debate. That is because he sees no better, though he welcomes, alternatives.

So far, most reviewers have not taken up his offer to debate. The few responders have taken issue in talking-head tone with his politics. This is ironic since “tone” is part of the very problem Mr. Judt identifies and criticizes. Our political and economic vocabulary has devolved into labels. Ill Fares the Land rips off and looks under the labels we hear others bandy about. It asks us to think for ourselves.

Right now, we hear people call President Obama a “socialist” or even “communist.” How many Americans these days know what those terms mean? And how many people can tell which parts of our government are conservative-libertarian and which are social-democratic? (And of those, how many know who supports which elements, Democrats or Republicans?) [Without referencing the budding Tea Party movement, Mr. Judt clearly hopes for more rational — and sustained – public activity than mere outcry.]

Mr. Judt joins Paine and a long list of individuals from St. Luke to Lenin and Tolstoy. Each burned with the question, what then must we do? The answer in our time cannot be, Mr. Judt argues, just to “turn again to the state for rescue.”

In our busy lives, we tend to debate such topics only as occasioned by immediate, daily mishap. We need to do more. “Our disability is discursive,” Mr Judt says. “We simply do not know how to talk about these things anymore.”

We have done more in the past. We founded our nation on a powerful manifesto — the Declaration of Independence. Our Founding Fathers did not dream up America in a vacuum. They distilled a new vocabulary out of European intellectual thought. They talked and published. They dared think new things. (One word in their new vocabulary was “democracy” — a dirty word until the American Revolution.)

Mr. Judt provokes thought. How could we have ever compared capitalism and communism? One describes economics; the other politics. Do we want capitalism everywhere? Not like today’s Russia (and China). Is social democracy sustainable economically — and can we avoid tyranny by majority?

Mr. Judt’s call for “recasting public conversation” makes this a book for conservatives as much as liberals. However, it targets young men and women of today. They need it — and Mr. Judt’s Ill Fares the Land will serve them far, far better than Lenin’s The Soviets at Work served my college-aged grandfather.

(This article also appeared in The Washington Times.)

Excerpts:

New York Review of Books

New York Times

Other reviews:

BBC Radio 3

NPR

Economist

New Statesman

Spectator

Monthly Review

The Nation

Times Literary Supplement 1

Times Literary Supplement 2

Financial Times

Guardian

Telegraph

Independent

Globe & Mail

Irish Times

New York Times 1

New York Times 2

Los Angeles Times

(Photo of Tony Judt from Pulse Media)

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary

In 1923, he visited Western Europe, still lying in the ruins of World War I. By 1925, he saw a “dying world… without faith, hope, character” [Witness, p. 195]. He came across a little book by

In 1923, he visited Western Europe, still lying in the ruins of World War I. By 1925, he saw a “dying world… without faith, hope, character” [Witness, p. 195]. He came across a little book by

While it may seem to parade in Marxist trappings, Ill Fares the Land is closer to the American book of another British transplant and radical,

While it may seem to parade in Marxist trappings, Ill Fares the Land is closer to the American book of another British transplant and radical,