Jun 17, 2014 0

C-SPAN: Cold War Era Spies

C-SPAN 3 aired “Cold War Era Spies” with new insight into the spy activities of Whittaker Chambers in the early 1930s, before the Hiss Case — more at WhittakerChambers.org.

Jun 17, 2014 0

C-SPAN 3 aired “Cold War Era Spies” with new insight into the spy activities of Whittaker Chambers in the early 1930s, before the Hiss Case — more at WhittakerChambers.org.

Nov 18, 2011 2

–

–

The Fear Within

The Fear Within

Spies, Commies, and American Democracy on Trial

By Scott Martelle

(New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011)

[This article appears on pp. 117-118 in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue, Volume 18, Number 3, of The Intelligencer magazine, published by the Association of Foreign Intelligence Officers [AFIO)]

In The Fear Within, Scott Martelle writes about a pre-McCarthy trial, which helped set the tone of the 1950s: Dennis v US. He mines his subject well. The nuggets he turns up command far more than a glimmer’s glance.

He does so by straddling the line between professional journalism and personal passion for his subject. From the outset, he notes dangers of “partisan rhetoric and passions” (p. ix). He discloses his own liberal leanings. “Had I lived through the 1930s, I likely would have been at some of the same meetings of political progressives” as his subjects. Yet, he promises, “this is a journalistic look at a moment in history” (p. xii).

Martelle reins in these contending forces thanks to longer-term concerns. His interest lies in politics over time. He is acutely aware of First Amendment freedoms of speech and of press. He sees how they can conflict with notions of sedition and treason. He calls this to his readers’ attention in his preface. There, he discusses a conflict stretching from the 1798 Alien and Sedition Act through to the present with the 2001 USA PATRIOT Act.

The book proper opens with passage of the 1940 Alien Registration Act (Smith Act). It moves on to the 1945 defections of Igor Gouzenko in Canada and Elizabeth Bentley in the U.S. By 1947, the government was mounting efforts against communist infiltration—with inter-agency cooperation foundering:

Mutual distrust between Attorney General Tom C. Clark and J. Edgar Hoover, his supposed underling at the FBI, colored how the Bentley revelations ultimately would be handled. The underlying problem was that Hoover’s investigations couldn’t corroborate Bentley’s claims; Clark wanted to push ahead with prosecutions. Both men wanted political cover from congressional inquiries—particularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)—if the Bentley allegations became public and it appeared that the Justice Department had done nothing. (p. 19)

HUAC’s began its Hollywood investigations later in 1947. News leaks of grand jury investigation into a “Red Spy Ring” followed in New York. The press was ready to print Bentley’s story by April 1948.

The arrest of twelve leaders of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) formed part of Justice’s political cover. Days before Bentley began testifying before HUAC, the FBI began making arrests in New York, Chicago, and Detroit. Within two weeks, they had rounded up William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Jack Stachel, John Williamson, Henry Winston, John Gates, Robert Thompson, Benjamin Davis Jr., Carl Winter, Irving Potash, Gil Green, and Gus Hall.

The next day, July 21, The New York World-Telegram published the Bentley story.

The year that followed was eventful. In 1949, three major trials related to Communism started: this trial of the Communist Twelve, the espionage trial of Judith Coplon, and the perjury trial of Alger Hiss. There were also deportation cases, like that of Alexander Stevens, AKA spymaster J. Peters. Abroad, Mao completed the communist takeover of China. Stalin tested a Soviet atom bomb.

The case against the twelve CPUSA leaders was the longest criminal trial to date in U.S. history. For those who enjoy the minutiae of court proceedings, The Fear Within provides a lively overview. The case included major surprises like last-minute contempt of court rulings against the defendants’ lawyers. It went all the way to the Supreme Court as Eugene Dennis, et al. v. United States. (It seems hard to believe that this trial never received a nickname like “the Commie Twelve” like the “Hollywood Ten.”)

As for accuracy in detail, I focus not on this case but on a related one mentioned in the book, the Hiss Case. I found two examples of hasty wording that lead to misinterpretation. First, Martelle writes about “allegations by Whittaker Chambers, a Time magazine editor and former Communist Party member who had been talking to the FBI about spies, including Alger Hiss, he had known while in the party” (p. 18). The phrase would be more accurate if it said “Chambers… whom the FBI had questioned in the 1940s about Alger Hiss and others he had known while in the party.” The author himself supports this correction: when recounting Chambers’ first testimony, he notes, “the people he named were not spies, he said” (p. 48). A second passage reads “The same grand jury that indicted the Communist Party leaders had indicted Alger Hiss on perjury charges, less than two weeks after Whittaker Chambers had revealed his ‘pumpkin papers‘” (p. 76). It would be more accurate to say, “…less than two weeks after Nixon paraded a leftover stash of microfilm from Chambers in front of the press, who dubbed the ‘Pumpkin Papers’.”

Such misreading may derive in part to a narrow bibliography. For the Hiss Case, Martelle cites solely John Chabot Smith‘s Alger Hiss: The True Story and not even Allen Weinstein‘s Perjury, which came out within two years in the 1970s and remains the definitive account. In fact, the author lists less than 50 books for research—a surprisingly small number, given the many books about the McCarthy Era.

Yet, Martelle’s book easily surmounts slips in shorthand and shorthanded references. Why?

Because he never lets passion—or fear—run unbridled when he writes. He keeps the long-term facts in mind. In Dennis v US, the government suspended the First Amendment based on fear of a small, impotent political party. Before that case had begun, CPUSA membership was seeing one-third turnover annually (p. 46). By the time most of the defendants got out of prison in 1955, the Party worldwide was about to suffer another, near-fatal blow from the Soviet heartland: Khrushchev would denounce Stalin. Martelle subscribes to the summation of British historian David Caute: “The government took a sledgehammer to squash a gnat” (p. 46).

Does undermining the First Amendment justify its cost? During intense moments, Americans have let their fears lead them to jettison freedoms, or degrees of freedoms. Over the longer term, however, those fears do not appear justified, claims Martelle.

Rather than slake thirst, this book should incite further interest from most readers, particularly students of colleges (or even high schools) lucky enough to have such relatively recent history taught in the classroom. The book may be a bit short on references, but the concerns it raises should impel readers to go out and read more.

There is one series of questions implied but left untouched. Had the U.S. government not gone on a witch hunt after the CPUSA after WWII, might homegrown Browderism have lived on? In which case, would a second strain of anti-Stalinist leftist have emerged? And would Browderism and Trotskyism have helped drown out Stalinism in the US?

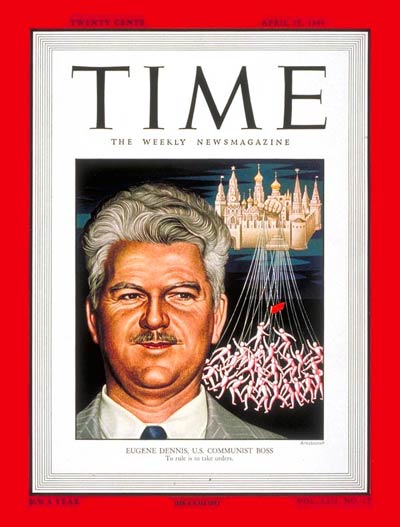

Special addendum: TIME cover story of Eugene Dennis: April 25, 1949:

Mar 14, 2011 4

America by Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith, and Flag

America by Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith, and Flag

By Sarah Palin

(New York: Harper, 2010)

Like a miracle — that is, miraculously in time for America’s biggest annual sales season — Sarah Palin called upon ghosts of Christmases past to fill the pages of her second book, America by Heart. Her publisher promised an “intimate and personal look” at the former Alaska governor by presenting reflections that “read like a bible of American virtues.” Instead, the goods delivered read like a cut-and-paste job: comments stuffed between quotes from famous people — often dead, thus unable to protest Palin’s (mis)treatment.

Among the ghosts Palin invokes is Whittaker Chambers — my grandfather. “I picked up the book Witness again for the first time in a long time. (One wonders: does she actually read books after picking them up?)

She quotes Chambers to help explain one of her ideas of “family” in America:

I was sitting in our apartment on St. Paul Street in Baltimore… My daughter was in her high chair. I was watching her eat. She was the most miraculous thing that had ever happened in my life… My eye came to rest on the delicate convolutions of her ear — those intricate, perfect ears. The thought passed through my mind: “No, those ears were not created by any chance coming together of atoms in nature (the Communist view). They could have been created only by immense design”… I did not then know that, at that moment, the finger of God was first laid upon my forehead. (Witness, pp. 16)

And the moral Palin draws?

“That is a wonderful way to put it: Our families lay the finger of God on our foreheads.”

Foreheads?

An eye, an ear, and a forehead all appeared in that passage — and the ear outshone the rest by more than a nose.

This ear passage (or the “ear-flap-based assumption” as Christopher Hitchens calls it) has become the most frequently quoted from Whittaker Chambers. In which case, Palin has merely copycatted what others quote most — literally “reflective,” but not insightful.

(Speaking of ear, I should speak out here for my poor aunt. That ear of hers must turn red every time someone reads this passage, or so I imagine. Since no one alive knows which ear, right or left, is the actual subject, the reddening must alternate like the lights at a railroad crossing, causing her further embarrassment and discomfort. How typical of my grandfather, failing to mention precisely which ear! Worse, if confronted today, he might remember the wrong ear, leading to yet another round of condemnation from Hiss supporters for faulty or faked memory.)

Her reason for quoting Chambers, Palin states, is that “by reminding us that we are fallible and fallen, families show us in concrete, everyday terms that which is not.”

If reminding us of our own fallibility was her intent in quoting from Witness, Palin should first have read the chapter called “The Story of a Middle Class Family.” Fallibility runs rampant here. Whittaker Chambers’ parents were unhappily married. His paternal grandfather drank. His maternal grandmother went mad, amidst the comforts of home. His father left the comforts of home to explore his bi-sexuality (actually, that tidbit appears in a biography). His brother committed suicide.

Then, having recounted his family’s failings, Palin could have quoted from “The Child,” in which Chambers wrote darkly:

“For one of us to have a child,” my brother had said… “would be a crime against nature.” …I agreed with my brother. There had been enough misery in our line. What selfish right had I to perpetuate it? And what right had any man and woman to bring children into the 20th-Century world? They could only suffer its inevitable revolutions or die in its inevitable wars.

At this point, Governor Palin could have countered Chambers’ pessimism with something sage composed by herself and drawn from her own family experience.

However, to quote from Witness is to pass up Chambers’ most famous essay for TIME magazine — which is also about family. The piece is “The Ghosts on the Roof,” written about the Yalta Conference. Controversial when published, it proved so prescient that TIME reprinted it three years later.

The family in “The Ghosts on the Roof” are ghostly members of the Romanov dynasty, who are watching Yalta proceed from the roof of the Livadia Palace.

The Romanovs express great admiration for Joseph Stalin:

“What statesmanship! What vision! What power! We have known nothing like it since my ancestor, Peter the Great, broke a window into Europe by overrunning the Baltic states in the 18th Century. Stalin has made Russia great again!… There he sits, so small, so sure. He is magnificent.”

A literary foil in the essay (the Muse of History) then pronounces:

“Your notions about Russia and Stalin are highly abnormal. All right-thinking people now agree that Russia is a mighty friend of democracy. Stalin has become a conservative. In a few hours the whole civilized world will hail the historic decisions just reached beneath your feet as proof that the Soviet Union is prepared to collaborate with her allies in making the world safe for democracy and capitalism. The revolution is over.” [emphasis added]

“Stalin has become a conservative.” At that particular moment, Chambers was mocking leftist and liberal Popular Front intellectuals, as he had in an earlier essay, “Revolt of the Intellectuals.” However, the line also hints at his own reservations about conservatism — feelings most conservatives (starting with

Nor did Krivitsky suppose… that the revolution of our time is exclusively Communist, or that the counterrevolutionist is merely a conservative… He believed, as I believe, that fascism (whatever softening name the age of euphemism chooses to call it by) is inherent in every collectivist form, and that it can be fought only by the force of an intelligence, a faith, a courage, a self-sacrifice, which must equal the revolutionary spirit that, in coping with, it must in many ways come to resemble… Counterrevolution and conservatism have little in common. In the struggle against Communism the conservative is all but helpless. For that struggle cannot be fought, much less won, or even understood, except in terms of total sacrifice. And the conservative is suspicious of sacrifice; he wishes first to conserve, above all what he is and what he has. You cannot fight against revolutions so.(Witness, p. 462)

After his defection in 1938, Whittaker Chambers considered himself wholly counterrevolutionist. Conservatives were his allies in the fight against Communism. Otherwise, they had “little in common.” (Of course, his writings cited here all predate the rise of the “New Right” or Conservatism championed by Buckley & Co.)

I cannot speak for the other ghosts quoted in America by Heart, but I can for my grandfather. Governor Palin: let the soul of Whittaker Chambers rest in peace. (Meanwhile, feel free to sit down and read his books.)

Nov 3, 2010 6

–

–

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary

By Richard M. Reinsch II

(Indianapolis: ISI Books, 2010)

(Reviewed by Gary Saul Morson)

(Excerpts from “He Heard the Screams,” published in the November 2010 issue of The New Criterion)

Why do otherwise decent people embrace ideologies that entail the killing of millions? What is the appeal that made so many people, especially intellectuals, support Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and Mao? Whittaker Chambers argued that if we are to combat the most monstrous evil in the history of the world—totalitarianism, as invented in the twentieth century by Lenin—we must understand what draws some people to it and makes others incapable of countering, or even understanding, its appeal.

[…]

It is no surprise, then, to learn from Richard Reinsch’s biography Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary that Chambers was deeply influenced by the greatest counterrevolutionary thinker of modern times, Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky, too, had once been a revolutionary conspirator, for which he had served four years in a Siberian prison camp. Both counter-revolutionaries rethought their convictions, embraced God, and became innovative conservative thinkers.

[…]

Chambers famously wrote that, in breaking with Communism and testifying against it, he was joining the losing side. I am not old enough to remember that testimony, but I do remember when both liberals and conservatives thought that the Soviet Union would soon outproduce us and, most likely, take over the world by the sheer power of example. So far as the Soviet Union goes, that thinking turned out to be completely mistaken. But, as Reinsch points out, Chambers’s point still holds. There are two ways in which freedom can lose—not only by challenge from without but also by gradual erosion from within. Freedom loses when people no longer value it. As recently as twenty-five years ago, most college professors I knew still believed in democracy, free elections, and free speech, even for their opponents. They stood up for Salman Rushdie. Now most have such contempt for hoi polloi that they do not see the point of allowing them to spread their ignorant lies. The rest of the faculty, who do cling to outmoded ideas of freedom, are embarrassed to express them.

Reinsch’s biography prompted me to read Witness for the first time. I discovered in it what I do not hesitate to call one of the great autobiographies of world literature. I could teach it alongside the autobiographical parts of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago and even Tolstoy’s Confession. Chambers thinks deeply and commands a unique and powerful style.

For that very reason, Reinsch’s treatment falls short. It’s not that he gets Chambers wrong. He’s accurate, but in the way that one of the better editions of SparkNotes conveys an accurate, if simplistic, version of a great author’s “message.” Part of the problem is Reinsch’s appalling prose. In one characteristic passage, he explains that

Chambers never charged his nation’s leaders with possessing overt sympathy to Communism. Rather, the Western leaders were unable to understand an enemy who pursued immanent ends with transcendent fervor due to their own paucity of spirit.

I had to read this sentence three times before I realized that, despite the syntax, “paucity of spirit” pertains not to the enemy but to the Western leaders. Such sentences make reading this book an irritating experience. Where Chambers writes with passion and palpability, Reinsch offers fuzz. His prose muffles the screams.

Gary Saul Morson is Chair of Slavic Languages & Literature at Northwestern University.

(Please click here to read the complete article)

Sep 1, 2009 1

Great Dames:

Great Dames:

What I Learned from Older Women

Marie Brenner

(New York: Crown Publishers, 2000)

Marie Brenner, who has penned the amazing, gripping investigative thriller The Insider among other books, put together one book I found rather misleading. Ostensibly, Great Dames is, according to the subtitle, about women she learned from. A few chapters into the book, however, we readers realize she did not know many of them very well. In fact, she relies heavily on anecdotes from others and from her subjects’s memoirs. Diana Trilling is a good example, and Brenner’s treatment of Whittaker Chambers a good case in point.