Nov 21, 2011 0

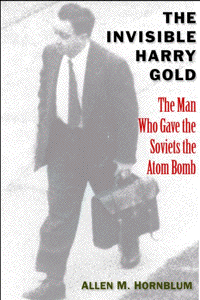

The Invisible Harry Gold: Allen Hornblum

–

A Real James Bond?

–

The Invisible Harry Gold:

The Invisible Harry Gold:

The Man Who Gave the Soviets the Atom Bomb

Allen M. Hornblum

(New Haven, Yale University Press, 2010)

[This article appears on pp. 116-117, Summer/Fall 2011 issue, Volume 18, Number 3, of The Intelligencer magazine, published by the Association of Foreign Intelligence Officers (AFIO)]

In The Invisible Harry Gold, author Allen M. Hornblum lets the story speak for itself. Nevertheless, undercurrents of irony exude throughout Harry Gold’s tale. While people like FBI director J. Edgar Hoover called him a “master Soviet spy” (p. ix), Mr. Hornblum attributes the secret to Gold’s success to his lack of personality.

James Bond he was not—or was he the real thing? The author calls him a “shy nebbish” (p. x and in “Gold Fingered,” Philadelphia City Paper). It was Gold’s personality that was invisible to most people. He consulted tapes and documents by Gold and others and consulted with nearly everyone alive who knew him. What emerges from this careful research is a three-part story of sin, contrition, and redemption—often in Gold’s own voice.

This tale begs readers to consider whether personal redemption can follow terrible sins and crimes—even for “the crime of the century.”

Harry Gold was an American agent in the Soviet underground. In the mid-1940s, he took atomic secrets from the hands of Dr. Klaus Fuchs and placed them in the hands of the Soviets. He was a courier, a go-between. Hand-offs from Fuchs occurred first in New York City, then in Los Alamos. Gold made tedious trips. He spent long hours waiting for covert meetings. Eventually, he bagged the big one: top secret documents from the Manhattan Project.

Eventually, too, the FBI got him. In May 1950, he confessed to his crimes. He cooperated fully. He named every name he knew. Many arrests followed, including David Greenglass, Morton Sobell, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

In his book, the author addresses the many attacks made upon Gold’s character by Rosenberg supporters over the years. Here, Mr. Hornblum demonstrates restraint. Rather than make asides to address them, he lets them come up in the story as they occurred. These personal attacks formed the background to both Gold’s sentencing (1951) and his later parole (1966). This book lets Gold and supporters do the talking.

Somewhat recently (2002), biographer Millicent Dillon published a “novel” called Harry Gold. That book’s blurb states that it “blends fact and fiction to chronicle the human drama of Harry Gold.” Ms. Dillon has two qualifications that make her an interesting person to write about him. In the 1940s, she was a staff writer for the Association of Scientists for Atomic Education in New York. She also was a physicist at Northrop Aircraft. That said, with all due respect, perhaps she should have taken Mr. Hornblum’s non-fiction approach. Mr. Hornblum avoids efforts at reaching “the psychological depth of Graham Greene‘s The Third Man, the taut pacing of All the President’ s Men, and the moral poignancy of Phillip Roth‘s I Married A Communist” (as Dillon’s book blurb claims). Of course, perhaps Ms. Dillon changed her conclusions in her research, like Allen Weinstein over the Hiss Case—and did not want to face Liberal attacks. Given the review by Victor Navasky‘s Nation magazine (bastion of support for the Rosenbergs and Hiss for decades), it seems she narrowly averted personal attacks on herself.

Hornblum’s chapter subheadings (usually quotes from actors in the story) become at times long and contrived. In fact, the writing seems almost to avoid artistry (in stark contrast to Ms. Dillon’s book). Here is a documentarian at work. Stripped down to bare essentials—events and actual statements of Gold and those around him—Hornblum proves that story alone can drive books.

There is an excellent epilogue that catches readers up on other actors in the book. It also covers new information that has come to light over the years. For example, the author notes Sobell’s amazing confession in 2008 about spying by himself, David Greenglass, and Julius Rosenberg.

Should Yale University Press ever republish the book, an appendix about the Soviet spy network in which Gold partook would help many readers, particularly with the passage of time. What were the real names of Gold’s handlers? Whom else did they handle? Where does Gold fit in with other famous names? While much of these details come up in the book, nowhere does it appear, assembled for easy reader reference. A social network chart would have helped, even as simplistic as those provided by “Namebase.org,” the online database published by Public Information Research, Inc.

Interestingly, while Mr. Hornblum tracks personal attacks on Gold’s physical appearance, he makes no mention of initial press reports about Elizabeth Bentley, dubbed the “Red Spy Queen.” Before photos of her came out, the press portrayed her as some kind of spy beauty, another Mata Hari. Nor does he note the same about Whittaker Chambers, though the Hiss Case comes up in the text. Using physical appearance to suggest moral character became a hallmark of spy cases in the Cold War era, used as much (if not more) by Left as by Right. In the two decades between the end of World War II and the Civil Rights movement, America exhibited prejudices nearly unthinkable today.

There is a movie to make here. One can hear the voice-over artist for PBS’s Frontline series or perhaps the BBC narrating this dark tale. Perhaps a film documentarian is up for the challenge of conjuring up the past with sight and sound as well.

Images of Harry Gold:

Life

Corbis

Smithsonian Magazine

Philadelphia Inquirer

ABC.es

Jerusalem Post