Mar 14, 2011 4

The Ghosts in Sarah Palin’s Book

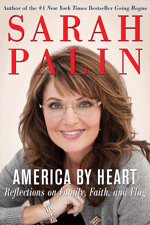

America by Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith, and Flag

America by Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith, and Flag

By Sarah Palin

(New York: Harper, 2010)

Like a miracle — that is, miraculously in time for America’s biggest annual sales season — Sarah Palin called upon ghosts of Christmases past to fill the pages of her second book, America by Heart. Her publisher promised an “intimate and personal look” at the former Alaska governor by presenting reflections that “read like a bible of American virtues.” Instead, the goods delivered read like a cut-and-paste job: comments stuffed between quotes from famous people — often dead, thus unable to protest Palin’s (mis)treatment.

Among the ghosts Palin invokes is Whittaker Chambers — my grandfather. “I picked up the book Witness again for the first time in a long time. (One wonders: does she actually read books after picking them up?)

She quotes Chambers to help explain one of her ideas of “family” in America:

I was sitting in our apartment on St. Paul Street in Baltimore… My daughter was in her high chair. I was watching her eat. She was the most miraculous thing that had ever happened in my life… My eye came to rest on the delicate convolutions of her ear — those intricate, perfect ears. The thought passed through my mind: “No, those ears were not created by any chance coming together of atoms in nature (the Communist view). They could have been created only by immense design”… I did not then know that, at that moment, the finger of God was first laid upon my forehead. (Witness, pp. 16)

And the moral Palin draws?

“That is a wonderful way to put it: Our families lay the finger of God on our foreheads.”

Foreheads?

An eye, an ear, and a forehead all appeared in that passage — and the ear outshone the rest by more than a nose.

This ear passage (or the “ear-flap-based assumption” as Christopher Hitchens calls it) has become the most frequently quoted from Whittaker Chambers. In which case, Palin has merely copycatted what others quote most — literally “reflective,” but not insightful.

(Speaking of ear, I should speak out here for my poor aunt. That ear of hers must turn red every time someone reads this passage, or so I imagine. Since no one alive knows which ear, right or left, is the actual subject, the reddening must alternate like the lights at a railroad crossing, causing her further embarrassment and discomfort. How typical of my grandfather, failing to mention precisely which ear! Worse, if confronted today, he might remember the wrong ear, leading to yet another round of condemnation from Hiss supporters for faulty or faked memory.)

Her reason for quoting Chambers, Palin states, is that “by reminding us that we are fallible and fallen, families show us in concrete, everyday terms that which is not.”

If reminding us of our own fallibility was her intent in quoting from Witness, Palin should first have read the chapter called “The Story of a Middle Class Family.” Fallibility runs rampant here. Whittaker Chambers’ parents were unhappily married. His paternal grandfather drank. His maternal grandmother went mad, amidst the comforts of home. His father left the comforts of home to explore his bi-sexuality (actually, that tidbit appears in a biography). His brother committed suicide.

Then, having recounted his family’s failings, Palin could have quoted from “The Child,” in which Chambers wrote darkly:

“For one of us to have a child,” my brother had said… “would be a crime against nature.” …I agreed with my brother. There had been enough misery in our line. What selfish right had I to perpetuate it? And what right had any man and woman to bring children into the 20th-Century world? They could only suffer its inevitable revolutions or die in its inevitable wars.

At this point, Governor Palin could have countered Chambers’ pessimism with something sage composed by herself and drawn from her own family experience.

However, to quote from Witness is to pass up Chambers’ most famous essay for TIME magazine — which is also about family. The piece is “The Ghosts on the Roof,” written about the Yalta Conference. Controversial when published, it proved so prescient that TIME reprinted it three years later.

The family in “The Ghosts on the Roof” are ghostly members of the Romanov dynasty, who are watching Yalta proceed from the roof of the Livadia Palace.

The Romanovs express great admiration for Joseph Stalin:

“What statesmanship! What vision! What power! We have known nothing like it since my ancestor, Peter the Great, broke a window into Europe by overrunning the Baltic states in the 18th Century. Stalin has made Russia great again!… There he sits, so small, so sure. He is magnificent.”

A literary foil in the essay (the Muse of History) then pronounces:

“Your notions about Russia and Stalin are highly abnormal. All right-thinking people now agree that Russia is a mighty friend of democracy. Stalin has become a conservative. In a few hours the whole civilized world will hail the historic decisions just reached beneath your feet as proof that the Soviet Union is prepared to collaborate with her allies in making the world safe for democracy and capitalism. The revolution is over.” [emphasis added]

“Stalin has become a conservative.” At that particular moment, Chambers was mocking leftist and liberal Popular Front intellectuals, as he had in an earlier essay, “Revolt of the Intellectuals.” However, the line also hints at his own reservations about conservatism — feelings most conservatives (starting with

Nor did Krivitsky suppose… that the revolution of our time is exclusively Communist, or that the counterrevolutionist is merely a conservative… He believed, as I believe, that fascism (whatever softening name the age of euphemism chooses to call it by) is inherent in every collectivist form, and that it can be fought only by the force of an intelligence, a faith, a courage, a self-sacrifice, which must equal the revolutionary spirit that, in coping with, it must in many ways come to resemble… Counterrevolution and conservatism have little in common. In the struggle against Communism the conservative is all but helpless. For that struggle cannot be fought, much less won, or even understood, except in terms of total sacrifice. And the conservative is suspicious of sacrifice; he wishes first to conserve, above all what he is and what he has. You cannot fight against revolutions so.(Witness, p. 462)

After his defection in 1938, Whittaker Chambers considered himself wholly counterrevolutionist. Conservatives were his allies in the fight against Communism. Otherwise, they had “little in common.” (Of course, his writings cited here all predate the rise of the “New Right” or Conservatism championed by Buckley & Co.)

I cannot speak for the other ghosts quoted in America by Heart, but I can for my grandfather. Governor Palin: let the soul of Whittaker Chambers rest in peace. (Meanwhile, feel free to sit down and read his books.)

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary