–

Sledgehammer and Gnat

–

The Fear Within

The Fear Within

Spies, Commies, and American Democracy on Trial

By Scott Martelle

(New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011)

[This article appears on pp. 117-118 in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue, Volume 18, Number 3, of The Intelligencer magazine, published by the Association of Foreign Intelligence Officers [AFIO)]

In The Fear Within, Scott Martelle writes about a pre-McCarthy trial, which helped set the tone of the 1950s: Dennis v US. He mines his subject well. The nuggets he turns up command far more than a glimmer’s glance.

He does so by straddling the line between professional journalism and personal passion for his subject. From the outset, he notes dangers of “partisan rhetoric and passions” (p. ix). He discloses his own liberal leanings. “Had I lived through the 1930s, I likely would have been at some of the same meetings of political progressives” as his subjects. Yet, he promises, “this is a journalistic look at a moment in history” (p. xii).

Martelle reins in these contending forces thanks to longer-term concerns. His interest lies in politics over time. He is acutely aware of First Amendment freedoms of speech and of press. He sees how they can conflict with notions of sedition and treason. He calls this to his readers’ attention in his preface. There, he discusses a conflict stretching from the 1798 Alien and Sedition Act through to the present with the 2001 USA PATRIOT Act.

The book proper opens with passage of the 1940 Alien Registration Act (Smith Act). It moves on to the 1945 defections of Igor Gouzenko in Canada and Elizabeth Bentley in the U.S. By 1947, the government was mounting efforts against communist infiltration—with inter-agency cooperation foundering:

Mutual distrust between Attorney General Tom C. Clark and J. Edgar Hoover, his supposed underling at the FBI, colored how the Bentley revelations ultimately would be handled. The underlying problem was that Hoover’s investigations couldn’t corroborate Bentley’s claims; Clark wanted to push ahead with prosecutions. Both men wanted political cover from congressional inquiries—particularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)—if the Bentley allegations became public and it appeared that the Justice Department had done nothing. (p. 19)

HUAC’s began its Hollywood investigations later in 1947. News leaks of grand jury investigation into a “Red Spy Ring” followed in New York. The press was ready to print Bentley’s story by April 1948.

The arrest of twelve leaders of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) formed part of Justice’s political cover. Days before Bentley began testifying before HUAC, the FBI began making arrests in New York, Chicago, and Detroit. Within two weeks, they had rounded up William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Jack Stachel, John Williamson, Henry Winston, John Gates, Robert Thompson, Benjamin Davis Jr., Carl Winter, Irving Potash, Gil Green, and Gus Hall.

The next day, July 21, The New York World-Telegram published the Bentley story.

The year that followed was eventful. In 1949, three major trials related to Communism started: this trial of the Communist Twelve, the espionage trial of Judith Coplon, and the perjury trial of Alger Hiss. There were also deportation cases, like that of Alexander Stevens, AKA spymaster J. Peters. Abroad, Mao completed the communist takeover of China. Stalin tested a Soviet atom bomb.

The case against the twelve CPUSA leaders was the longest criminal trial to date in U.S. history. For those who enjoy the minutiae of court proceedings, The Fear Within provides a lively overview. The case included major surprises like last-minute contempt of court rulings against the defendants’ lawyers. It went all the way to the Supreme Court as Eugene Dennis, et al. v. United States. (It seems hard to believe that this trial never received a nickname like “the Commie Twelve” like the “Hollywood Ten.”)

As for accuracy in detail, I focus not on this case but on a related one mentioned in the book, the Hiss Case. I found two examples of hasty wording that lead to misinterpretation. First, Martelle writes about “allegations by Whittaker Chambers, a Time magazine editor and former Communist Party member who had been talking to the FBI about spies, including Alger Hiss, he had known while in the party” (p. 18). The phrase would be more accurate if it said “Chambers… whom the FBI had questioned in the 1940s about Alger Hiss and others he had known while in the party.” The author himself supports this correction: when recounting Chambers’ first testimony, he notes, “the people he named were not spies, he said” (p. 48). A second passage reads “The same grand jury that indicted the Communist Party leaders had indicted Alger Hiss on perjury charges, less than two weeks after Whittaker Chambers had revealed his ‘pumpkin papers‘” (p. 76). It would be more accurate to say, “…less than two weeks after Nixon paraded a leftover stash of microfilm from Chambers in front of the press, who dubbed the ‘Pumpkin Papers’.”

Such misreading may derive in part to a narrow bibliography. For the Hiss Case, Martelle cites solely John Chabot Smith‘s Alger Hiss: The True Story and not even Allen Weinstein‘s Perjury, which came out within two years in the 1970s and remains the definitive account. In fact, the author lists less than 50 books for research—a surprisingly small number, given the many books about the McCarthy Era.

Yet, Martelle’s book easily surmounts slips in shorthand and shorthanded references. Why?

Because he never lets passion—or fear—run unbridled when he writes. He keeps the long-term facts in mind. In Dennis v US, the government suspended the First Amendment based on fear of a small, impotent political party. Before that case had begun, CPUSA membership was seeing one-third turnover annually (p. 46). By the time most of the defendants got out of prison in 1955, the Party worldwide was about to suffer another, near-fatal blow from the Soviet heartland: Khrushchev would denounce Stalin. Martelle subscribes to the summation of British historian David Caute: “The government took a sledgehammer to squash a gnat” (p. 46).

Does undermining the First Amendment justify its cost? During intense moments, Americans have let their fears lead them to jettison freedoms, or degrees of freedoms. Over the longer term, however, those fears do not appear justified, claims Martelle.

Rather than slake thirst, this book should incite further interest from most readers, particularly students of colleges (or even high schools) lucky enough to have such relatively recent history taught in the classroom. The book may be a bit short on references, but the concerns it raises should impel readers to go out and read more.

There is one series of questions implied but left untouched. Had the U.S. government not gone on a witch hunt after the CPUSA after WWII, might homegrown Browderism have lived on? In which case, would a second strain of anti-Stalinist leftist have emerged? And would Browderism and Trotskyism have helped drown out Stalinism in the US?

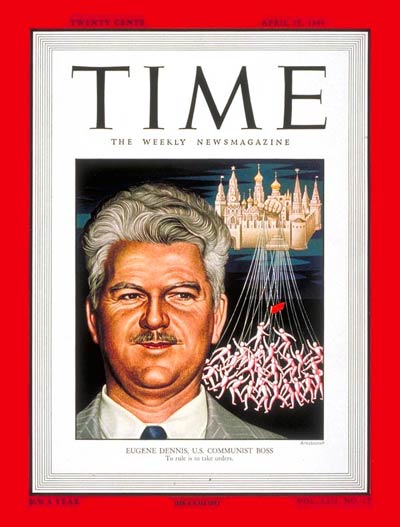

Special addendum: TIME cover story of Eugene Dennis: April 25, 1949:

America by Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith, and Flag

America by Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith, and Flag

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary

Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Counterrevolutionary